Sometimes a diamond in the rough should remain in the rough.

After flunking out of one college during her senior year and then getting expelled from another (possibly because she was caught repeatedly sneaking a boy into her room through a 3rd story window), Judy Henske made her way from the chilly Midwest out to sunny California in 1959 and joined the beatnik folkie scene. She had inherited a banjo from a former paramour who decamped to India and, after learning how to play the instrument, scored herself a residency at a club in Los Angeles called The Unicorn. Her powerful voice and unusual look made quite an impression.

When Jac Holzman, the founder of Elektra Records, first spotted Henske, she was up on the stage, all 6 foot something of her, with stringy black hair down to her waist, wearing a rubber duck-hunting jacket, belting out a folk song and stomping her foot so hard to keep the beat he feared she would break right through the stage. He wanted her on Elektra, and what Holzman wanted he usually got.

Elektra was a small label, known in those early days of its existence for its devotion to folk and world music — as well as its impeccable taste. People often bought records unheard based only on the Elektra name. Knowing it would be a good home, Judy Henske signed with the upstart indie.

With contract in hand, Jac Holzman made it a priority to spruce up Judy’s image. His wife, Nina, co-ran the label and she did a full makeover on Henske, hiding the unkempt hair beneath a fashionably bobbed wig, getting her out of blue jeans and the rubber jacket and into a fancy dress and sparkly jewelry. The intent was to turn her into a kind of cocktail singer, like Peggy Lee, but with folk songs. To that end, a jazz big band was hired to back her up in the studio.

Her 1963 debut album was, for the most part, well-received by critics. But it wasn’t Judy.

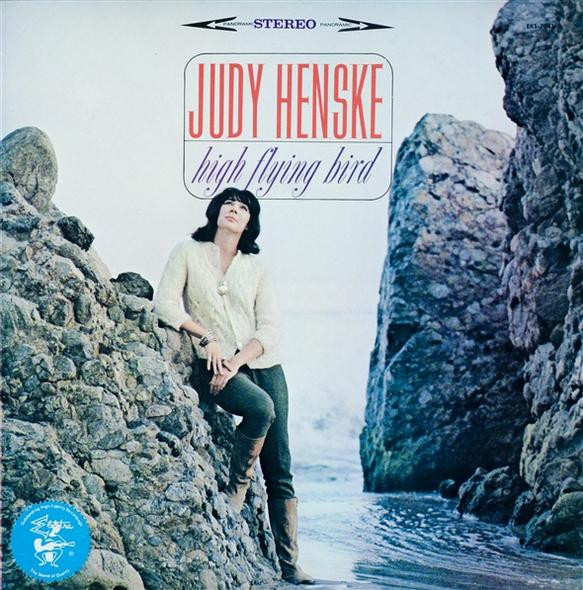

For her next album — released in 1964 — gone was the wig, the dress, and the big band. Henske was backed by a small combo with guitar and banjo back to the fore. The album was titled after its opening track, a song called “High Flying Bird,” written by Billy Edd Wheeler (best known in later years for Johnny and June’s duet, “Jackson,” and for “Coward Of The County” by Kenny Rogers). Although “High Flying Bird” wasn’t a hit, it proved extremely influential with the musicians of the 1960s and many artists covered the song after hearing Judy’s record — most notably, Jefferson Airplane, who performed “High Flying Bird” at the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967, and Richie Havens, who played the song two years later at Woodstock.

As rock & roll slowly pushed folk aside, Henske never quite found her niche in the new music scene, but she had already made an indelible mark, just by being herself.